Newsletter

Recently the Two Red Roses Foundation received as a generous gift to the collections a staircase by Louis Sullivan (1856-1924), the Chicago architect acclaimed for his mastery uniting ornament and form in shaping the image of the early skyscraper and, more broadly, the concepts around early modern design that permeated the American Arts and Crafts movement. In lieu of a complete building, a staircase seems a particularly apt object to represent his achievements in building not only new, taller skyline for Chicago and other cities nationwide, but establishing a legacy that would influence nationwide a generation of architects and designers including his one-time employee, Frank Lloyd Wright (1867-1959). Sullivan’s work, through its lyrical balance of form and function, elegantly bridged the worlds of nineteenth century ornament and the new industrial technologies that saw towering, steel-framed buildings awash with electric lights and staircases paired with the innovation of mechanized elevators.

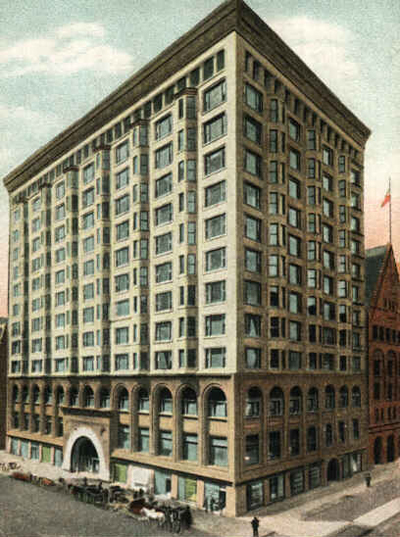

Following his brief architectural experiences under Frank Furness (1839-1912) in Philadelphia and William LeBaron Jenney (1832-1907) in Chicago, in 1880 Sullivan began working with architect and engineer Dankmar Adler (1844-1900), establishing a partnership with him in 1883. In the fifteen years they worked together, their firm completed nearly 180 buildings across the country including the Chicago Stock Exchange (constructed 1893-94) from which this staircase was salvaged. Commissioned by Chicago businessman Ferdinand W. Peck (1848-1924), the 13-story Exchange building eschewed the style of neoclassicism traditional to Beaux Arts training and popularized in the overall design of Chicago’s World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 to instead express Sullivan’s holistic approach to ornament expressive of natural forms and symbolic of the structure of the building.

Drawing inspiration from Emersonian ideas of nature and earlier designers including the Englishman Owen Jones (1809-1874), whose Grammar of Ornament (1856) illustrated the stylization of natural elements as well as designs from non-European sources, Sullivan created his own particular blends of abstracted motifs distilled from imagery of seed pods, tendrils, and flowers. Although the formal elements of this staircase are not novel, meeting his principle of “where function does not change, form does not change,” the copper-plated cast iron surfaces of its newel posts, risers, and balustrade are a rich tapestry of novel reliefs repeating interlocking geometries and vegetative whorls. While these suggest the fluid, organic dynamic of Art Nouveau styling, they are yet distinctly contained and ordered as the product of architectural design in service to the whole.

Originally this staircase was one of many installed in two locations between the 4th and 12th floors of the Exchange building, flanking a central hallway with banks of elevators that also provided access to the office spaces on these floors. As in Sullivan’s other buildings, his patterns, echoed throughout the interior in stenciled friezes, grillwork, and fixtures, were equally reflected on the exterior of the building, treating the whole of the structure with common and complementary themes as a unifying leitmotif. Like the work of his more progressive peers including a younger generation of Arts and Crafts designers, Sullivan’s achievements in creating his own system of ornament stood in defiance of Beaux Arts neoclassicism and as a rallying cry for a new, distinctly American style befitting the age.

While the demolition of the Chicago Stock Exchange in 1972 meant the loss of one of Adler & Sullivan’s greatest buildings, its demise prompted a renewed fervor in Chicago’s historic preservation movement as fragments of the lost building were subsequently distributed to public and private collections around the country. With the installation of this staircase in the Museum of the American Arts and Crafts Movement, we will join the Art Institute of Chicago and the Metropolitan Museum of Art among other institutions in representing the artistic legacy of the Chicago Stock Exchange and Louis Sullivan’s vision for design and architecture at the turn of the twentieth century.