Newsletter

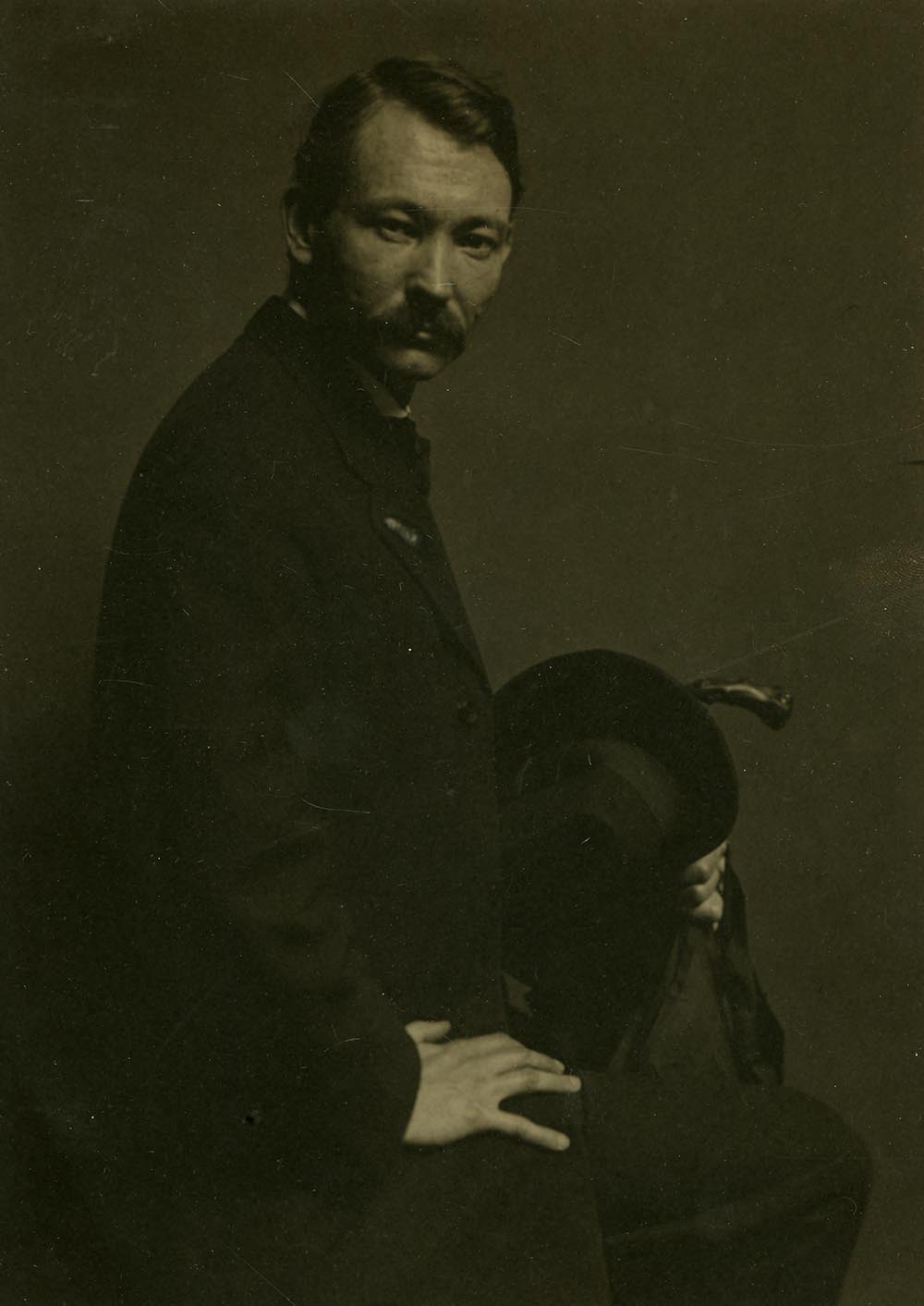

Fig. 1 - Adolf de Meyer, French, 1868-1946, Gertrude Käsebier, c. 1900, platinum print, 8 5/8 x 7 1/8 inches, Library of Congress.

The year 2020 marks the centennial anniversary of many significant events, such as Babe Ruth signing with the New York Yankees, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s publication of This Side of Paradise, and – probably the most talked about this year – the ratification of the 19th Amendment, giving women the right to vote. In honor of this historic event, the Two Red Roses Foundation (TRRF) is committed to raising awareness of the many women artists represented in its collection. Prominent among them is Gertrude Käsebier, an American who was instrumental in defining modern photography (Fig. 1).

Born Gertrude Stanton on May 19, 1852, in Fort Des Moines, IA, Käsebier’s interest in photography developed later in life. Her 1874 marriage to Eduard Käsebier, a shellac importer from German aristocracy, afforded her the financial stability to study art after raising their children. Originally enrolling in 1889 at New York’s Pratt Institute to study portrait painting, Käsebier became fascinated with photography after a trip to Europe in 1894, where she spent time in Germany learning the chemical aspects of the medium. Returning to the States, she apprenticed for a photographer in Brooklyn, eventually opening her own portrait studio in Manhattan in 1897. It was during this time in Brooklyn that Käsebier honed her talents, building upon her studies in painting to become one of most important portrait photographers associated with the pictorialist movement. One noteworthy example is the simple yet powerful portrait of the painter Robert Henri (Fig. 2), which appeared in Gustav Stickley’s The Craftsman, the leading periodical of the Arts and Crafts movement.

Fig. 4 - Gertrude Käsebier, Mother and Child, 1903, platinum print, 6 ¾ X 7 inches, TRRF Collection.

Käsebier quickly became a leading figure in pictorial photography, a movement that shared the Arts and Crafts ideals of simplifying compositions and emphasizing the hand of the maker. Pictorialists sought to assert the medium’s status as an art form by manipulating photographs to achieve qualities of fine art, such as soft focus and dramatic lighting. They likewise strove to simplify their figure studies, landscapes, still lifes, and genre scenes of extraneous elements and details, creating artistic images that were often evocative, mysterious, or dramatic. These qualities are visible in many of Käsebier’s works, especially in her portraits of women and children. In The Crystal Gazer and Mother and Child (Figs. 3 and 4), she employed blurring effects similar to painted brush strokes. Portrait (Miss N) and Dorothy (Figs. 5 and 6) combine emotional intensity with a painterly soft focus.

Fig. 7 - Gertrude Käsebier, Indian Chief (Whirling Horse), 1902, photogravure, from Camera Notes, July 1902, 4 ⅞ X 6 ⅜ inches, TRRF Collection.

One of Käsebier’s earliest portraits, Indian Chief (Whirling Horse) – a half-length portrait of a member of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show – garnered Käsebier a great deal of attention, as it was included by The Camera Club of New York in their publication Camera Notes, edited by renowned photographer Alfred Stieglitz (Fig. 7). Between 1899 and 1902, Stieglitz selected seven works by Käsebier for Camera Notes, more than any photographer. He also included her as a founding member of the Photo-Secession, a group described by Stieglitz as “Americans devoted to pictorial photography in their endeavor to compel its recognition… as a distinctive medium of individual expression.” When the Photo-Secession eventually moved away from pictorialism, Käsebier resigned from the group but continued to work in this style until retiring in 1927.

Käsebier’s powerful works will be among other pictorialist photographs displayed at the Museum of the American Arts and Crafts Movement. The forthcoming exhibition Lenses Embracing the Beautiful: Pictorial Photographs from the Two Red Roses Foundation will feature more than 150 stunning photographs and rare books of pictorial photography, from the 1890s to the 1940s.

![Fig. 5 - Gertrude Käsebier, Portrait (Miss N) [Evelyn Nesbit], 1903, Photogravure, from Camera Work, January 1903, 7 ¾ X 5 ¾ inches, TRRF Collection.](https://www.tworedroses.com/newsletters/images/newsletter08032020/fig5.jpg)